Nigeria, Others Piled Up $860bn Debts In 2020 – W/Bank

Low income countries, including Nigeria, piled up a debt of $860 billion last year, following COVID-19 outbreak, the World Bank has said.

In a report, the World bank said: “Governments around the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with massive fiscal, monetary, and financial stimulus packages”.

The pandemic forced governments to pump money into health emergency and measures to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 on the poor and vulnerable, this act of releasing money into the system, the World Bank said, resulted in huge debt burdens on low-income countries.

As a result of this development, the debts of low-income countries rose by 12 per cent to a record $860 billion in 2020, a new World Bank report said.

Prior to the pandemic, many low- and middle-income countries were already in vulnerable positions, “with slowing economic growth and public and external debt at elevated levels”.

External debt stocks of low- and middle-income countries combined rose by 5.3 per cent in 2020 to $8.7 trillion. According to the new International Debt Statistics 2022 report, “an encompassing approach to managing debt is needed to help low- and middle-income countries assess and curtail risks and achieve sustainable debt levels”.

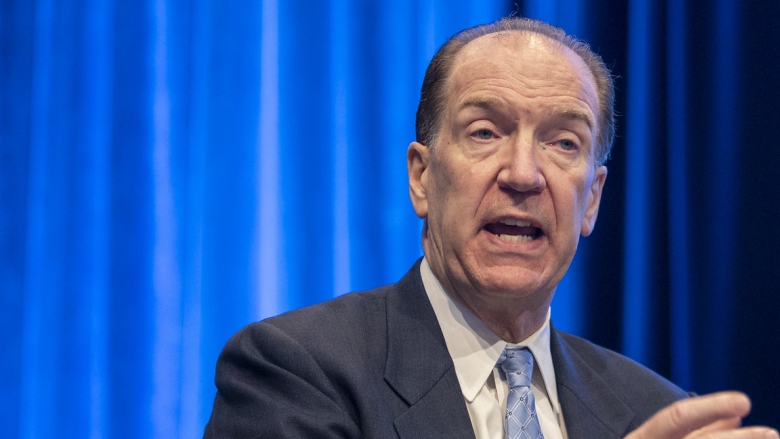

World Bank Group President David Malpass said a comprehensive approach to the debt problem, including debt reduction is needed for “swifter restructuring and improved transparency,” pointing that “sustainable debt levels are vital for economic recovery and poverty reduction”.

The worsening debt indicators were widespread and these impacted countries in all regions. According to the report, the deteriorating indicators cut across “all low- and middle-income countries, the rise in external indebtedness outpaced Gross National Income (GNI) and export growth”.

The report added that “low- and middle-income countries’ external debt-to-GNI ratio (excluding China) rose to 42 per cent in 2020 from 37 per cent in 2019, while their debt-to-export ratio increased to 154 per cent in 2020 from 126 per cent in 2019″.

The G20 launched the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in April 2020 to provide temporary liquidity support for low-income countries at the behest of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in response to the unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic.

In November 2020, the G20 agreed on a Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI. This is an initiative to restructure unsustainable debt situations and protracted financing gaps in DSSI-eligible countries

Before then, the G-20 countries had agreed to extend the deferral period through the end of 2021.

“Overall, in 2020, net inflows from multilateral creditors to low- and middle-income countries rose to $117 billion, the highest level in a decade.

“Net debt inflows of external public debt to low-income countries rose 25 per cent to $71 billion, also the highest level in a decade. Multilateral creditors, including the IMF, provided $42 billion in net inflows, while bilateral creditors accounted for an additional $10 billion”.

Carmen Reinhart, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank Group said “economies across the globe face a daunting challenge posed by high and rapidly rising debt levels. Policymakers need to prepare for the possibility of debt distress when financial market conditions turn less benign, particularly in emerging market and developing economies.”

He said: “Greater debt transparency is critical in addressing the risks posed by rising debt in many developing countries. To facilitate transparency, International Debt Statistics 2022 (IDS 2020) was expanded to provide more detailed and disaggregated data on external debt than ever before”.

The data from the IDS 2020 now gives the breakdown of a borrowing country’s external debt stock to show the amount owed to each official and private creditor, the currency composition of this debt, and the terms on which loans were extended.

For DSSI-eligible countries the, data set was expanded to include the debt service deferred in 2020 by each bilateral creditor and the projected month-by-month debt-service payments owed to them through 2021.

The World Bank will also publish soon a new Debt Transparency in Developing Economies report that takes stock of debt transparency challenges in low-income countries and lays out a detailed list of recommendations to address them.

International Debt Statistics (IDS) is a longstanding annual publication of the World Bank featuring external debt statistics and analysis for the 123 low- and middle-income countries that report to the World Bank Debt Reporting System (DRS).

Adesina said Nigeria must “decisively” resolve its debt challenges to ignite economic growth.

In September, the Debt Management Office (DMO) said Nigeria’s total public debt (federal and state governments) climbed to N35.46 trillion at the end of the second quarter of 2021.

Speaking on Monday in Abuja at the opening of a two-day mid-term ministerial performance review retreat, Adesina said Nigeria’s debt service to revenue ratio is high.

The AfDB president, however, acknowledged that the debt-to-GDP ratio remains “moderate”.

Adesina said economic resurgence is possible when Nigeria removes “structural bottlenecks” that limit the revenue-earning potential of non-oil sectors.

“Nigeria must decisively tackle its debt challenges. The issue is not about the debt-to-GDP ratio, as Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 35% is still moderate. The big issue is how to service the debt and what that means for resources for domestic investments needed to spur faster economic growth,” he said.

“The debt service to revenue ratio of Nigeria is high at 73%. Things will improve as oil prices recover, but the situation has revealed the vulnerability of Nigeria’s economy. To have an economic resurgence, we need to fix the structure of the economy and address some fundamentals.

“Nigeria’s challenge is revenue concentration, as the oil sector accounts for 75.4 % of export revenue and 50 % of all government revenue.

“What is needed for sustained growth and economic resurgence is to remove the structural bottlenecks that limit the productivity and the revenue earning potential of the huge non-oil sectors.”